Massive Investments and “Big Fund” Initiatives

China’s policy-makers see electronic components as strategic to national security and economic strength. In recent years, they have launched huge government-backed investments to boost the domestic industry:

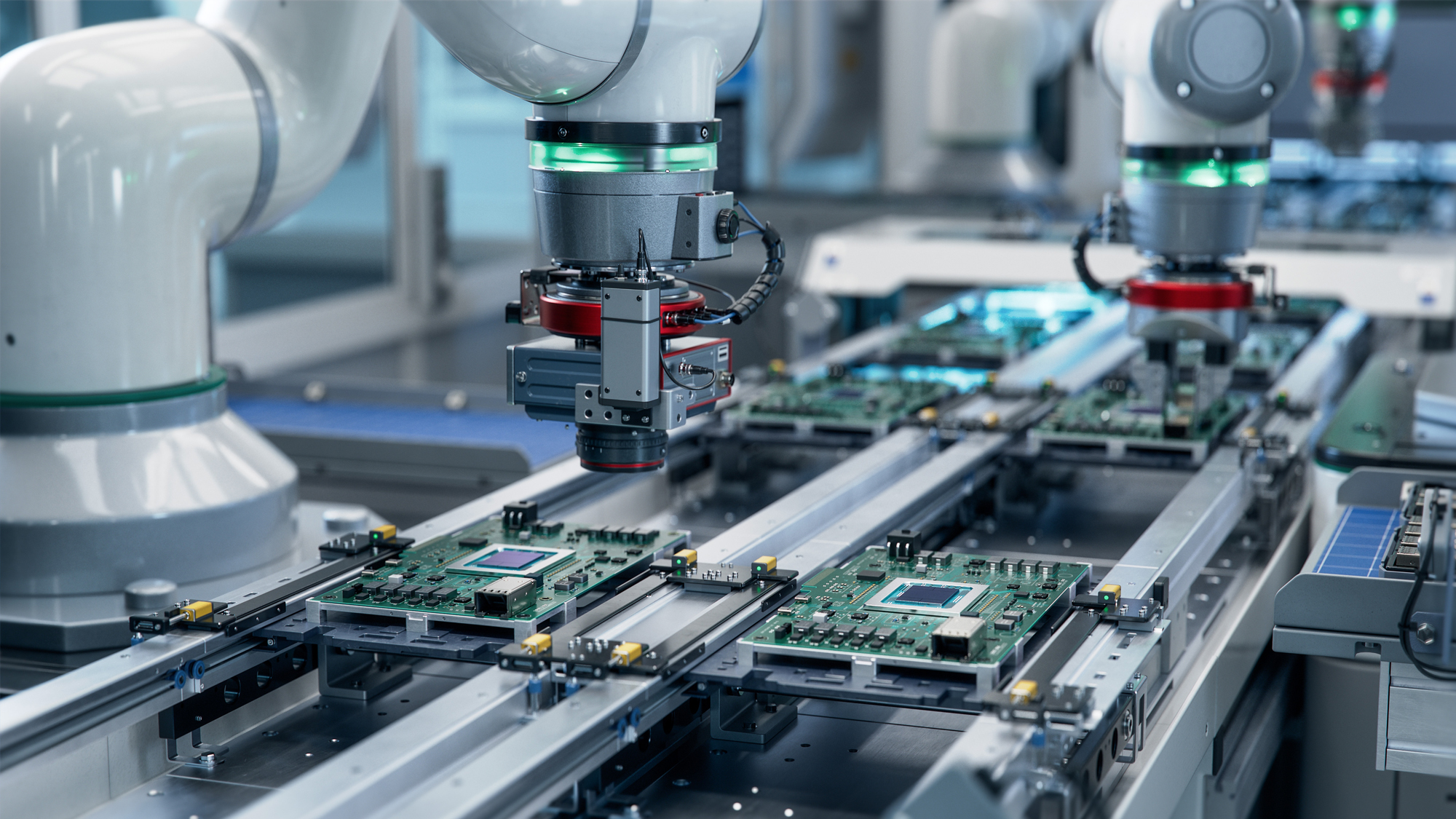

National IC Investment Fund (“Big Fund”) Phase III: In May 2024, China established the third round of its semiconductor industry fund with an enormous ¥3440 billion (≈$47 billion) in capital. This makes it the largest semiconductor fund in China’s history, exceeding the combined size of the first two phases. The Big Fund III’s mandate is to invest across the chip supply chain – with an emphasis on fab construction, critical chip manufacturing equipment, and key component technologies. By early 2025, it had already made an initial investment of ¥164 billion into two sub-funds targeting chip fabrication. For component buyers, this signals that China will heavily subsidize and expand domestic production of chips and related components, potentially increasing supply and competition in the medium term.

Strategic Emerging Industries Plans: The Chinese government has included semiconductors, new materials (for components), AI, and new energy vehicles (which drive demand for power electronics) in its 14th Five-Year Plan as priority sectors. Local governments offer incentives like cheap land, tax holidays (often 5-year tax exemptions for chip firms), and research grants to companies that set up component factories in their region. Dozens of new projects – from wafer fabs in Guangzhou to capacitor plants in Jiangxi – have broken ground under these policies.

“Little Giant” Programs: Apart from big players, China also supports smaller specialized firms through the “Specialized and Innovative Little Giants” program. Many component makers (like niche sensor companies, connector manufacturers, etc.) have received this status, which comes with financial support and easier access to credit. The goal is to cultivate a base of innovative SMEs in components that can fill gaps and become future champions.

The impact of these investments is beginning to show: more Chinese companies are entering the components market, and existing ones are scaling up faster than they could on their own. For example, Hua Hong Semiconductor (a major chip foundry) received additional state investment to build new 12-inch fabs, which will churn out more made-in-China chips for consumer and automotive uses. As these funded projects come online, global buyers might see greater availability of China-made chips and possibly lower prices due to increased competition.

Export Controls and Trade Measures

On the flip side of encouraging import substitution, China has implemented export controls on certain materials and components, both as a security measure and as a tit-for-tat response to Western restrictions:

Critical Metals Export Restrictions: In July 2023, China’s Ministry of Commerce imposed export controls on gallium and germanium products, essential for high-speed chips, optical fibers, and military components. Exporters now require special licenses. In August 2024, controls were expanded to include antimony and advanced composite materials. By February 2025, China added tungsten, molybdenum, bismuth, indium, and tellurium – metals crucial in semiconductors, aerospace, and defense – to the list. These moves leverage China’s dominance in raw materials (e.g., it produces most of the world’s gallium and germanium) and have forced global component makers to seek alternatives or stockpile, creating future supply risks.

Tech Export Bans (Equipment and Chips): Although China is generally pro-export, it has mechanisms in place to restrict certain technologies. Since 2020, China has reviewed exports of tech with national security implications – like AI algorithms and advanced drones. In hardware, discussions emerged in 2023 around restricting exports of surveillance camera chips and AI accelerators, mirroring U.S. import bans. While no broad bans on mainstream components had been enacted by 2024, future restrictions on strategic items (e.g., AI or power chips) remain possible and should be monitored by procurement teams.

Tariffs and Trade Agreements: China has strategically used tariffs to support its semiconductor sector. Import duties on some fab equipment were waived, while export tariffs on rare earths were considered but not implemented as of 2024. Trade agreements like RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) have reduced tariffs on electronic components between China and Asian nations, streamlining regional supply chains.

Chinese officials clarify that “export control is not an export ban” – licensed trade remains possible, but it adds regulatory friction and unpredictability. For example, foreign companies can still import gallium from China, but must navigate a licensing process. These developments are viewed as countermeasures to U.S. export controls, which since late 2022 have restricted China’s access to advanced semiconductors and fab tools.

From a procurement perspective, this evolving environment marks a shift toward politicized supply chains. Both Chinese and Western policies can abruptly affect component availability. Buyers should monitor regulatory changes, consider supply redundancy, and potentially qualify secondary sources – especially for components or materials heavily sourced from China. Being proactive can help mitigate delays and maintain continuity in critical categories.

Self-Reliance and Import Substitution

Central to China’s policies is the theme of “自主可控” (self-reliant and controllable) supply chains. This strategy has driven broad efforts to reduce dependency on foreign—particularly U.S.—technology for critical electronic components:

Localization of Supply Chain: Chinese manufacturers are encouraged (and sometimes mandated, for state projects) to use domestic components. This has created a burgeoning domestic market for Chinese component suppliers, giving them scale. For example, in government telecom infrastructure, there’s a push to use routers and servers built with Chinese semiconductors and passives. The auto industry too, under policies to foster “China-made smart cars,” is incentivized to use Chinese chips and sensors where possible (e.g., some EV makers have switched to domestic MCU chips when feasible).

Standards and Regulation: China is also developing its own technical standards in certain areas, which can favor local players. For instance, the BeiDou navigation satellite system (an alternative to GPS) has spurred demand for BeiDou-compatible RF components and modules – an area where Chinese companies stepped up. In 5G and now 6G research, China’s active role in standards means its companies are at the table early, potentially giving them a leg up in supplying the needed components when those standards roll out.

Import Reduction Metrics: By policy, many sectors have set goals like “increase domestic component usage by X%.” In 2022, a target was circulated to raise the self-sufficiency rate in semiconductors to 70% by 2025. While that exact figure may be optimistic, it drives behavior—large amounts of resources are being funneled into achieving even incremental improvements. As a result, Chinese companies are developing domestic alternatives for nearly every component category: for example, local FPGA chips (from Gowin Semiconductor), domestic EDA software, Chinese-brand oscilloscopes, and electronic design tools. This comprehensive push means that global firms now face a new wave of competitors—well-funded, state-supported, and increasingly sophisticated.

For international buyers, one immediate effect is that Chinese demand for imported components might decrease in certain areas because they use domestic ones, potentially freeing up some global supply. On the other hand, Chinese companies not buying foreign components could hurt economies of scale for those foreign suppliers, possibly raising prices. It’s a complex equation.

One clear outcome: Chinese component makers will eventually seek markets abroad once the domestic market saturates. We are already seeing this with products like solar inverters, batteries, and some electronics – Chinese firms first dominate at home, then offer their products overseas at compelling prices. Procurement teams might soon find Chinese-made alternatives being pitched for virtually every type of component, even high-tech ones, as a result of these self-reliance policies driving maturity.

What Buyers Should Monitor Going Forward

Given these policy dynamics, here are a few pointers for procurement and supply chain professionals to navigate the landscape:

Keep Informed on Policy Changes: Dedicate part of your risk management to tracking US, EU, and Chinese trade policy updates. For example, if the U.S. announces new chip restrictions or China announces a new controlled material, map out which of your components might be affected. Subscribe to industry news or consulting briefings that summarize these moves in plain language.

Evaluate “China+1” for Critical Inputs: If you rely heavily on a component that is primarily made in China (or a material only sourced there), consider qualifying a backup source in another country as insurance. The PCB industry example is instructive – many companies are now ensuring they have PCB suppliers in Taiwan or Southeast Asia besides China, in case trade frictions worsen. However, recognize that Chinese companies themselves are often part of the China+1 solution (e.g., Chinese PCB firms in Vietnam), so it may still be Chinese-owned, just not China-located.

Leverage Chinese Policies to Your Advantage: China’s push to produce more domestically means there may be increased supply capacity and possibly government subsidies that lower costs. Be open to new Chinese suppliers that emerge from these programs – they might offer very competitive pricing (sometimes initially undercutting to gain market share). Also, if you have manufacturing in China, local governments might offer incentives for using local suppliers – sometimes joint development funds or faster customs clearance. It could align with your cost-down initiatives.

Plan for Compliance: If you do business in both the West and China, ensure your sourcing choices comply with all sides. For instance, using a Chinese telecom component could restrict selling into U.S. government projects due to NDAA regulations. Conversely, exporting a high-end oscilloscope to China might require an export license. It’s a delicate balance – but good planning and legal guidance can allow you to benefit from Chinese tech while staying within rules. Many companies adopt a strategy of segmenting products by market – a version for China use with all-Chinese components (to satisfy Chinese rules) and a version for Western use that might use more Western parts (to avoid any bans).

Long-Term Partnerships: If you identify Chinese suppliers critical to your supply chain, build strong relationships and communicate about policy impacts. Chinese companies themselves are navigating these waters; if you collaborate closely, they might alert you to upcoming issues (like “we need an export license to send you this item next quarter, let’s work together on it”). Having a transparent partnership can help mitigate surprises.

In summary, China’s policy environment is actively molding the component industry – injecting huge resources on one hand, and wielding control levers on the other. This creates both opportunities (new sources, potential cost benefits) and risks (sudden supply cut-offs, compliance pitfalls). The key for international buyers is to stay agile and informed.

Call to Action: Make policy monitoring a core part of your procurement strategy. Set up a quarterly review of how geopolitical shifts could impact your components supply. Engage with experts or consultants if needed to interpret these moves. By understanding the direction of China’s policies – from the massive Big Fund investments to the latest export control list – you’ll be better prepared to secure your supply chain and even turn policy changes into strategic advantages for your organization.